Tatiana Trouvé was born in Italy, grew up in Senegal and has been primarily based in Paris for the previous few a long time. Working throughout installations, sculpture and drawing, she creates an imaginary world the place reminiscence, phantasm, theatre, nature, the artist’s studio, and the inside and the outside intersect. Her enigmatic work is commonly disquieting, hovering in an unsure temporal house. This involves the fore in her solo exhibition, The Nice Atlas of Disorientation, curated by Jean-Pierre Criqui, opening on the Centre Pompidou in Paris this week. The present consists of variously sized drawings (together with 4 new large-scale works), that are suspended from the ceiling and hanging on the partitions, in addition to a ground drawing and sculptures positioned behind a curtain. In an unfolding, virtually apocalyptic drama, varied preoccupations are explored, from the primary lockdown of the Covid-19 pandemic to fires in Brazil’s Amazon rainforest. The Artwork Newspaper met Trouvé in her studio in Montreuil, on the jap periphery of Paris, in Might.

The Artwork Newspaper: Why have you ever titled your exhibition The Nice Atlas of Disorientation?

Tatiana Trouvé: It’s a title that always options in my work. I selected it for the exhibition as a result of it captures the intuitive method of making work. When one is within the studio, there’s all the time this state of disorientation that permits us to proceed to make issues and be between two worlds. And when one is disoriented, one is attentive to issues that one wouldn’t discover earlier than—like being within the mountains and searching on the stars for steering. It’s when one is disorientated that attention-grabbing issues begin to occur.

How does this manifest in your method of responding to the structure of the Centre Pompidou’s house?

I like this house quite a bit as a result of it might resemble my drawings a bit—it’s a big glass dice the place the inside and exterior are fairly permeable. So I needed to make an set up, beginning with my drawings, the place the sculptures are solely seen from the skin. The sculptures are behind a curtain and contained in the exhibition they’re backlit and seem as silhouettes, turning into extra like drawings. The drawings are all hung at completely different heights [and] typically the customer can stroll beneath them, to lend the impact of the house floating. What I’m making an attempt to do is disorientate the customer’s method of trying; it’s a sport that’s not simply frontal however that makes us raise or decrease our heads, look from proper to left. There’s additionally a big drawing everywhere in the ground composed of various diagrams and readings of the world, from the Dreaming maps by the [Australian] Aboriginals to diagrams of chaos and cells. I need folks to get misplaced inside it and for it to create connections with the drawings.

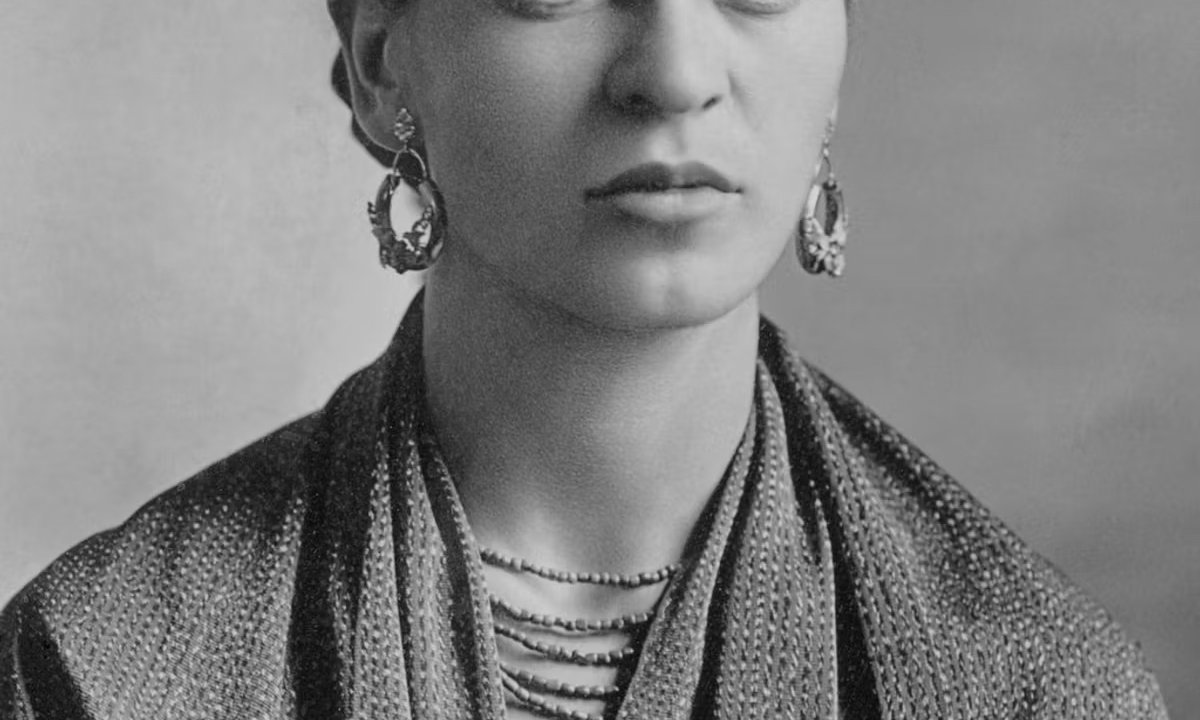

Trouvé’s Untitled from a brand new collection of drawings, Les Dessouvenus (the forgotten). The semi-abstract impact is the results of making use of a colored pencil drawing to paper that has had bleach utilized Picture: © Thomas Lannes; Courtesy of Gagosian Gallery; © Adagp Paris

The present opens along with your collection From March to Might, made throughout the first Covid-19 lockdown in 2020. Every day, you drew an image on a printout of the entrance web page of the day before today’s newspaper, beginning with the French journal Libération, revealed the day earlier than lockdown was imposed. Might you elaborate in your methodology?

The entrance web page of Libération gave me the thought for the entire collection as a result of its headline, Le Jour Avant, was a reference to the movie The Day After Tomorrow. I assumed that if the day earlier than was already like that, what is going to the day after be like? It was like getting into an invisible, imaginary conflict, not understanding what was going to occur with this virus. For the entrance pages, I had choice standards: international locations that have been very affected by the pandemic, the place folks have been enclosed like us, which was straightforward as a result of the pandemic was worldwide. Secondly, I needed unbiased press, not tabloids or propaganda newspapers. What spoke to me typically was like a revelation about what I used to be doing within the studio or in my life. For instance, I drew my canine Lula on the entrance cowl of the Guardian. It’s humorous as a result of I’ve made a collection of sculptures referred to as The Guardian [of portraits of imaginary people in the form of chairs] and Lula can be my studio’s guardian. I drew an extended queue of individuals ready outdoors a grocery store getting into the canine’s abdomen, a bit just like the wolf in Little Crimson Driving Hood. Different entrance covers appeared to go nicely with the surroundings of my studio so I drew parts of my studio onto them. The final entrance cowl can be from Libération, so the collection is sort of a loop. The 56 drawings comprise one work; there’d be no that means in separating them—it’d be like ripping pages out of a diary.

Did the pandemic have an effect on your work in different methods?

Maybe it did unconsciously. It’s troublesome to say as a result of maybe I don’t have the mandatory distance but. I remorse that international locations didn’t take extra radical initiatives as a result of we’re residing in a interval that’s an ecological disaster. I discover it catastrophic that gross sales of boats and personal planes have soared. Every time issues torment us, or convey us ache or pleasure, it should come out in what we do. I’ve had ecological consciousness as a citizen for years and beforehand made decisions in my work, comparable to not utilizing resin or Plexiglas.

I compose areas, universes and worlds, making different pictures seem, onto which I can venture one thing

Tatiana Trouvé

You’ve stated that you just contemplate your self above all as a sculptor despite the fact that you’re equally recognized on your drawings.

For me, a drawing is a sculpture; I see little or no distinction between my sculptural work and my drawing. My sculptures usually seem in my drawings and my drawings usually encourage my installations. A whole lot of issues in my drawings don’t have anything to do with portray. I discolour industrially colored paper with bleach, so I exploit merchandise like a sculptor does, and I exploit blue and black Indian ink. I lighten the paper with the bleach to create stains and from these stains I compose areas, universes and worlds, making different pictures seem, onto which I can venture one thing. It’s like making an attempt to learn the residue in a espresso cup. Considered one of my new drawings, L’Escamoteur, borrowing the title of a well-known portray by Hieronymus Bosch of a magician performing a trick, is a world of reflections and illusions with drape-like material, a flying dove, an imperfect circle. I’ve a complete atlas of pictures, from my installations, sculptures, images or issues that I acquire, that haunts me and returns quite a bit. Though there’s the absence of the human determine, I’ve the impression that human beings are very current in my work. For me, [the works in the series] The Guardian are portraits of individuals; I don’t depict the determine however their needs or fears by books, garments and objects, as if the chairs are inhabited by ghosts.

Trouvé’s Il mondo delle voci (2022) depicts a forest, “a really talkative place”, she says, superimposed with a 3 dimensional type. “I introduced my copper sculptures into this residing world,” Trouvé explains

Picture: © Florian Kleinefenn. Courtesy of Gagosian Gallery; © Adagp Paris

Your drawing Il mondo delle voci (2022) depicts a forest superimposed with one in all your sculptures. What was the impetus behind it?

For me, the forest is a really talkative place the place there are a number of voices. The crops speak—scientists have discovered methods to file their vibrations evoking communication—and through droughts, they scream. I needed to translate the power inside this ecosystem and I introduced my copper sculptures into this residing world. I needed to mix constructive and damaging pictures, like when one appears to be like at one thing for a very long time, then closes one’s eyes and sees contrasts. The drawing portrays actual forests, even my very own backyard, in addition to imaginary ones. One other drawing that I’m making might be a imaginative and prescient of parts underwater but in addition parts of a forest—it’s not a romantic panorama however the smoke of issues burning. It’s very troublesome to say what this portray is making an attempt to divulge to us and it’s that complexity that pursuits me.

How do you suppose rising up in Dakar, the place you have been entranced by tales of spirits referred to as djinn, influenced your work?

In Dakar, one used to say that the djinn lived within the gardens of the house. There’s definitely a dimension of magical thought in my work and that’s in all probability one thing that harks from my childhood. My father was a professor of structure but in addition a sculptor. Like a number of youngsters of musicians and artists, I used to be rapidly confronted by this [creative] universe and for me it was straightforward to attract and sculpt early on.

What position does instinct play in the way you strategy concepts?

I’ve an thought initially for a drawing however all the alternatives that I make afterwards are guided by my instinct. Even initially of my profession, I made issues intuitively. Once I made the Bureau of Implicit Actions [1997-2007, which began by collecting employment rejection letters], I used to be a penniless artist, and not using a studio, simply an infinite void. I requested myself: “Am I nonetheless an artist despite the fact that I’m invisible to all people?” It was one thing intuitive to suppose that out of this void I’ll make one thing and provides type to it. An artist lives quite a bit by the eyes of others however we’ve to be taught to do with out [recognition]. It’s each being in a solitary and unbiased world and but needing confrontation.

Tatiana Trouvé’s Notes on Sculpture (2021) Non-public assortment, Berlin. Picture: © Florian Kleinefenn; © Adagp, Paris, 2022

Considered one of your collection is titled Intranquillity—what does this convey to you?

I really like the phrase “intranquillity”. It’s an invention of [the Portuguese writer and poet] Fernando Pessoa—not being tranquil however not being irritated both. For me, intranquillity is a type of focus. One must make oneself obtainable to that notion. I belief the customer: whether or not or not they’re captured by my work, every individual might understand it differently. I’m not proposing a collection of occasions to entertain the customer however organising a universe and the customer is free to enter it or refuse it.

Biography

Born: 1968, Cosenza, Calabria, Italy; raised Dakar, Senegal

Lives: Paris

Training: Villa Arson, Good; Ateliers 63 (now de Ateliers), Haarlem, the Netherlands

Key reveals: 2015 Central Park, New York (Public Artwork Fund); 2014 Musée d’Artwork Moderne et Contemporain, Geneva; 2010 Bienal de São Paulo; 2009/2010 Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst, Zurich; 2008 Centre Pompidou (after successful the 2007 Prix Marcel Duchamp); 2007 Venice Biennale and Palais de Tokyo, Paris; 2003 Venice Biennale and CAPC Musée d’Artwork Contemporain, Bordeaux

Represented by: Gagosian, König Galerie (Berlin) and Perrotin (Asia)

• The Nice Atlas of Disorientation, Centre Pompidou, Paris, 8 June-22 August; Tatiana Trouvé, Gagosian, Paris, 8 June-3 September