Within the March 1978 concern of Excessive Occasions journal, Susan Sontag gave a uncommon interview about her new e book, known as On Images. “It’s not about pictures,” Sontag saved saying. Equally, she insisted to The New York Occasions that she was not writing about pictures, however about “the best way we at the moment are”. “The topic of pictures is a type of entry to up to date methods of feeling and considering,” she stated.

Sontag struggled to be understood. Images was thought of an illegitimate artwork kind by a lot of her artwork critic contemporaries. However Sontag understood how pictures acted as an “exemplary exercise” in society—one which uniquely explored “the whole lot that’s good and ingenious and poetic and pleasureful”, she instructed Excessive Occasions.

“Sontag was prescient in her understanding of pictures’s function in up to date life,” says Mia Fineman, a pictures curator on the Metropolitan Museum of Artwork in New York, who has contributed to the primary ever illustrated version of Sontag’s now seminal 1977 e book, to be launched on 13 September by the Folio Society. “Whereas most critics had been worrying about pictures’s standing as artwork, Sontag was occupied with pictures in relation to client tradition.”

On Images includes a group of essays that Sontag initially printed within the New York Overview of Books between 1973 and 1977. Though she was an excellent scholar—she studied variously on the College of California, Berkeley, the College of Chicago and Harvard—Sontag’s writings didn’t come from the closed loop of academia. She was writing for the individuals pounding the pavements of New York, sitting in bars or cafes or on the subway, in search of a fast mental buzz.

Every essay took her round six months to jot down; every phrase, then, was fastidiously thought of, each sentence sweated over. However her lyrical dialogue of summary ideas like illustration and actuality stay a needed lesson for any aspiring interpreter of artwork and life.

The essays are revealing of the creator. Sontag was the daughter of Jewish New Yorkers of Polish and Lithuanian descent who had constructed a cushty residence in Lengthy Island. Though she got here from a well-off household, Sontag confronted many early challenges. In an interview with the Guardian newspaper, she spoke of a father virtually at all times away on enterprise, and a chilly, distant mom who “flinched if you happen to touched her”. Her father died of tuberculosis when was simply 5. Quickly after leaving residence, on the age of 17, Sontag agreed to marry one in every of her lecturers after a ten-day courtship. She quickly grew to become a mom, however the marriage solely lasted 9 years.

All through her youth, Sontag needed to carve out a profession of her personal making, in an trade peopled and managed by older males. Fineman admits that, studying the e book immediately, one discerns “logical inconsistencies and self-contradictions”. They assist us to know the lady who wrote them.

Sontag’s phrases at the moment are routinely quoted in any debate in regards to the affect pictures has had, and continues to have, on each aspect of recent life. Early within the e book, she calls photographic imagery “essentially the most irresistible type of psychological air pollution”. She wrote: “Needing to have actuality confirmed and expertise enhanced by images is an aesthetic consumerism to which everyone seems to be now addicted.”

Sontag died of leukaemia in New York in 2004, three years into the Battle on Terror and 6 years earlier than the delivery of Instagram. However already within the Seventies, Sontag understood that, with a digicam in hand, “having an expertise turns into similar with taking {a photograph} of it”.

The e book was not solely effectively obtained. To this present day, pictures theorists usually assume Sontag was an opponent of the medium. “There was a widespread misunderstanding of her elementary perspective towards the medium,” Fineman says. “Many critics believed that she was in opposition to pictures, that she thought the medium was terribly harmful or harmful. In truth, Sontag liked occupied with images.”

The primary devoted pictures exhibition at a serious UK cultural establishment got here as late as 2003, when Tate Fashionable staged Merciless and Tender: The Actual within the Twentieth-Century {Photograph}. Sontag was writing virtually three many years earlier, when many teachers had been nonetheless engaged within the restricted debate of whether or not pictures can “honestly” replicate actuality—whether or not a picture can ever be “actual”.

Sontag noticed by way of it. She was one of many first theorists to jot down about pictures’s potential to deceive and manipulate, its efficiency when deployed as propaganda, its capability to take advantage of the reality. She known as the digicam “a predatory weapon”. She noticed: “Pictures, which can’t themselves clarify something, are inexhaustible invites to deduction, hypothesis, and fantasy.”

This, Fineman says, was Sontag at maybe her most prophetic. “Her insights about photos of atrocity and compassion fatigue stay painfully related immediately. She understood as effectively that pictures displays the whole lot that’s harmful and polluting and manipulative in our life.”

Writing in an introduction to the brand new version, Fineman expands on this level. “On Images explores the moral implications of digicam imaginative and prescient within the realm of reportage,” she writes. “The voyeurism and complicity concerned in taking and images of atrocity, and the hazards of compassion fatigue, of changing into desensitised to pictures of struggling.”

In New York and London, the established pictures neighborhood—the gatekeepers of the trade—stay to this present day pretty conservative in outlook, instinctively immune to new concepts. It’s value remembering how the gatekeepers of Sontag’s day responded to On Images.

In March 1978, the Worldwide Heart of Images in New York held a symposium to debate the e book. Through the session, the Heart’s director, Cornell Capa, stated: “Up to now, photographers have both ignored the e book, denied having learn it, or are livid about private implications that they resent.”

A month later, the critic Colin Westerbeck wrote in Artforum journal: “Sontag is prejudiced. She doesn’t see images as particular person works in the identical approach {that a} bigot doesn’t consider blacks or Italians or Jews as particular person individuals.”

However Sontag’s concepts stay as resonant in 2022 because the day she wrote them. “The facility and originality of Sontag’s e book lie in her eagerness to interact with pictures’s promiscuity,” Fineman writes. “Its voraciousness, and the profound function the medium has performed in shaping the contours of recent consciousness, for higher or worse.”

The Folio Society version of On Images by Susan Sontag, printed 13 September, 224pp, £90.00, hb

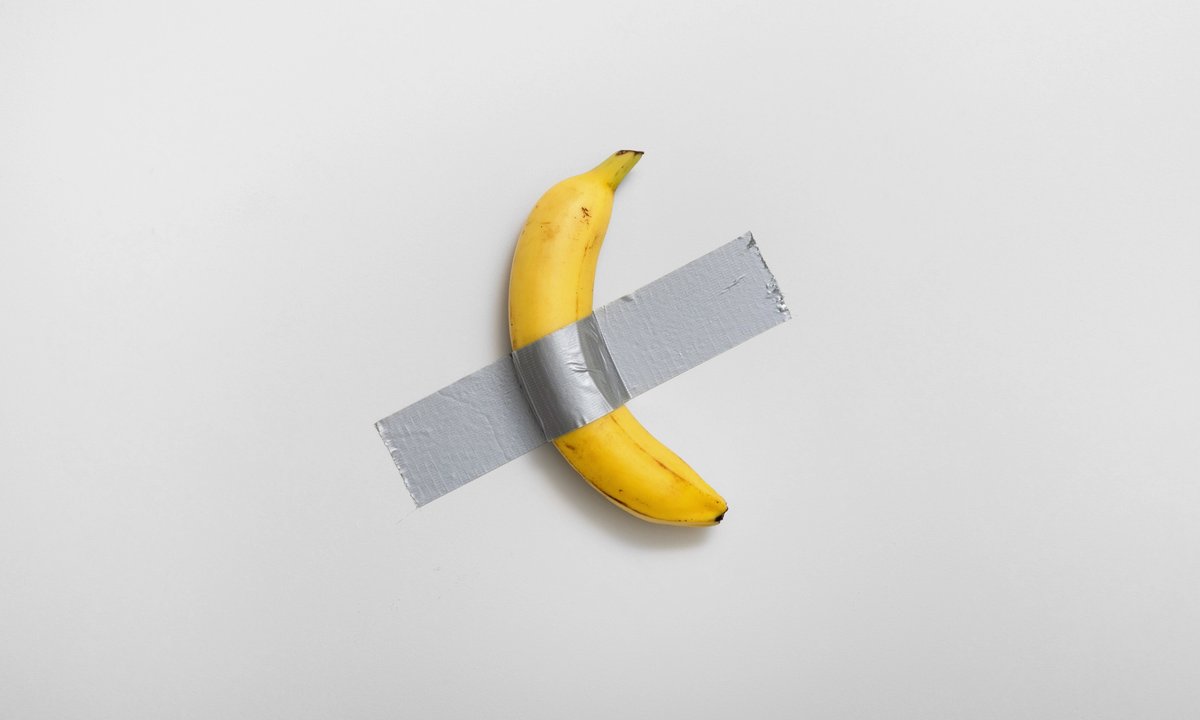

A number of pages from On Images by Susan Sontag.

courtesy The Folio Society