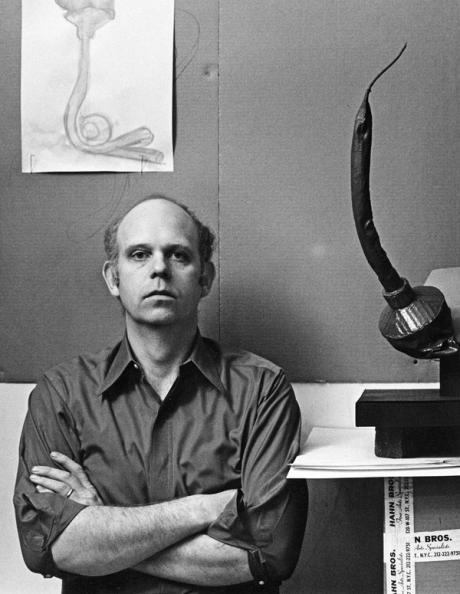

Claes Oldenburg defied the foundations of Summary Expressionism, making sculptures and sewn creations from supplies discovered on the streets of New York. Ultimately, he crafted abnormal objects on a grand public scale within the US and Europe however chafed when his colossal sculptures have been known as Pop Artwork as debates raged over whether or not they have been monuments, municipal advertising or simply monstrous.

Oldenburg died at 93 from issues after a fall, 13 years after the passing of Coosje van Bruggen, his spouse and collaborator since 1977, who shared credit score on their work collectively. These sculptures conquered public areas, however his early work was within the trenches, on the streets and within the shopfronts of Manhattan within the early Sixties, when artists clawed their manner past abstraction. One mission, from 1967, was an rectangular gap that appeared to await a corpse in Central Park behind the Metropolitan Museum. Earlier than then, he had opened The Retailer (1961-62) on the Decrease East Facet, which for a month bought variations of abnormal objects in plaster and paint that mocked an artwork market which ignored what he made. “Nothing is irrelevant,” Oldenburg wrote in a pocket book entry. “All the pieces can be utilized.”

His objective at The Retailer “was to place color into area, to make color really feel tangible,” he recalled. “It was meant to be a murals, and not likely a retailer.” Nonetheless, Alfred Barr, the director of MoMA, acquired 1962’s Two Cheeseburgers, with All the pieces (Twin Hamburgers) in plaster and paint.

Artwork “happenings”, which Oldenburg organised with Allan Kaprow, Purple Grooms, Lucas Samaras and others, have been free-form gatherings (not but known as efficiency artwork) the place individuals wore the artwork, normally sewn by Oldenburg’s first spouse, Patty Mucha. His mushy sculptures, which she created out of cloth, questioned the sturdiness of artwork. A mushy lavatory in vinyl, with its Comfortable Bathroom (1966), appeared designed to shock or trigger disgust, or each.

Nevertheless it wasn’t Pop Artwork, Oldenburg burdened. “The pondering round it and the feelings transcend that. It wasn’t an try and make feedback on consumerism or capitalism or no matter. It was an try and make artwork, to make type, out of the supplies round us,” he stated. Laconic, terse and trenchant, Oldenburg advised the critic David Sylvester in 1965, in a wide-ranging interview, that “if you happen to’re all in favour of type slightly than in sculpture as some slim concept of what sculpture might be, why shouldn’t there be mushy type in addition to arduous?”

I consider sculpture usually as type and area or mass and area, and that permits me to incorporate something as sculpture—chairs as sculpture or bottles or bathtubs or something

Claes Oldenburg

“There may be one other notion that’s not allowed in sculpture, that sculpture might be perishable or made from perishable supplies,” he stated. “I don’t know, this most likely goes again to some spiritual idea of sculpture: it ought to final, it ought to endure and so forth. However I consider sculpture usually as type and area or mass and area, and that permits me to incorporate something as sculpture—chairs as sculpture or bottles or bathtubs or something.”

Objections to his mushy sculpture, he advised Sylvester, “should be some kind of sexual factor. Maybe sculpture is concerned with erections and so forth. Sculpture has at all times had a sort of a masculine high quality and portray has at all times been thought to be a softer artwork… all my items have been someplace in between.”

Ominous big ice lotions

Oldenburg usually stated that he grew to become an artist as a result of he might draw. Born in Stockholm in 1929, the son of a diplomat who grew to become the Swedish consul in Chicago, Oldenburg noticed himself as an American of Swedish origin. He had stated that he was conceived within the US however his mom returned to Sweden for his delivery. He attended Yale and the Artwork Institute of Chicago faculty, then lasted six months as a reporter in Chicago. “I couldn’t see myself spending a lifetime writing meaningless stories about meaningless occasions,” he advised MoMA in 1969.

After opening (and shutting) The Retailer, Oldenburg labored on drawings that he known as Proposed Colossal Monuments. His sketches of imagined grand sculptures have been as ominous as they have been whimsical—an enormous ice cream bar to interchange the Pan Am constructing, an enormous teddy bear in Central Park that demarcated class boundaries and, in what he known as “on a regular basis crap” in three dimensions, a phallic-shaped deflated purple drainpipe in Toronto.

A turning level was Lipstick (Ascending) on Caterpillar Tracks (1969), an enormous tube of make-up on a tank-like chassis. College students who knew Oldenburg’s “colossal monument” drawings requested the thinker Herbert Marcuse, visiting Yale, what would possibly occur if constructions prefer it—mocking and feminising a army car through the Vietnam Warfare—have been truly constructed. As Oldenburg recalled, Marcuse stated that may imply the top of capitalist society.

Anticipating that final result, the scholars commissioned an actual model of Lipstick and sneaked the completed work into the campus, setting it up on Beinecke Plaza. Oldenburg, who constructed it free of charge, stated that Yale officers, fearing one thing worse, allowed Lipstick to remain, though it was later eliminated, remade with extra sturdy supplies and relocated to a different web site at Yale, the place it nonetheless stands right this moment.

A parade of gargantuan works adopted—from an ice cream, Dropped Cone, in Cologne to the 45-foot black metal Clothespin in Philadelphia, two adjoined sticklike shapes that Oldenburg stated echoed Constantin Brancusi’s The Kiss. Sculptures of black mice that he made in Los Angeles within the Sixties led to Disney comparisons—but Oldenburg’s scale and light-hearted juxtapositions of components recommend the creativeness of a surrealist Dr Seuss.

If Oldenburg sought a broader public with that huge scale, it didn’t work in a single day. In Cleveland, Ohio, a colossal rubber stamp, Free Stamp (1985), first commissioned by the Amoco petroleum firm, was rejected by British Petroleum, which acquired Amoco whereas Oldenburg was constructing the work. Ultimately, native authorities put it in a park. In Miami, an enormous fruit bowl break up into a number of elements, Dropped Bowl with Scattered Slices and Peels, was condemned in 1990 as a hazard. And in Kansas Metropolis, the place Oldenburg and van Bruggen produced big shuttlecocks on a garden on the Nelson-Atkins Museum in 1994, a columnist within the Kansas Metropolis Star known as them inappropriate, though the newspaper’s personal artwork critic admired them.

The custom in public sculpture is to create one thing hierarchical which is up on a pedestal. Individuals are shocked when that custom is turned on its head

Claes Oldenburg

“The custom in public sculpture is to create one thing hierarchical which is up on a pedestal,” stated Oldenburg in a 1992 NPR interview. “Individuals are shocked when that custom is turned on its head and as a substitute you get a easy object that most individuals most likely don’t really feel belongs on a pedestal. However in fashionable occasions, such an object is extra acceptable than, say, an equestrian statue.”

“Fairly often a public sculpture is utilized by folks to advertise their very own causes. Politicians will use it to make a case which might name consideration to themselves,” the artist famous.

“Coosje and I really feel that someway it wouldn’t be proper to place up one thing that everyone would agree on, that we’ve got a accountability as artists to create one thing that has a little bit of an edge, that lies a bit forward of the final consciousness, so when that’s transferred into public artwork, it does make folks shocked typically, although they do get used to it,” Oldenburg advised NPR.

There have been numerous critics who dismissed these works as edge-less advertising gambits for the cities that acquired them. Oldenburg had gone Pop and down-market, and acquired a château in France, they stated. In 1961, he had written, “I’m for artwork that’s placed on and brought off like pants, which develops holes like socks, which is eaten like a chunk of pie, or deserted with nice contempt like a chunk of shit.” Some requested if this was the identical artist.

A number of years after van Bruggen’s loss of life, Oldenburg returned to small-scale sculptures. His 2017 collection Shelf Life was a set of 15 ensembles whose components recommend his earlier work and are counterposed with Seventeenth-century Dutch work. All the valedictory present at Tempo Gallery, New York, was acquired by the Museum of Effective Arts (MFA) Boston. The MFA’s director, Matthew Teitelbaum, stated “I began to consider the notion of an older artist, late in life, enthusiastic about achievement—reconciling, celebrating, raging towards it. It made me consider Matisse’s cut-outs or Rembrandt’s final nice self-portraits.”

Requested in 2017 which artists he admired, Oldenburg cited René Magritte for his 1929 portray The Treachery of Photos (Ceci n’est pas une pipe), a frank differentiation between an object and the depiction of an object. “The artwork is made as artwork – we’re making type, we’re making concepts, we’re making emotions. The artwork might seek advice from many different issues, however the artwork is in itself the creation,” Oldenburg burdened. “Though we name it a hamburger, it’s not a hamburger.”

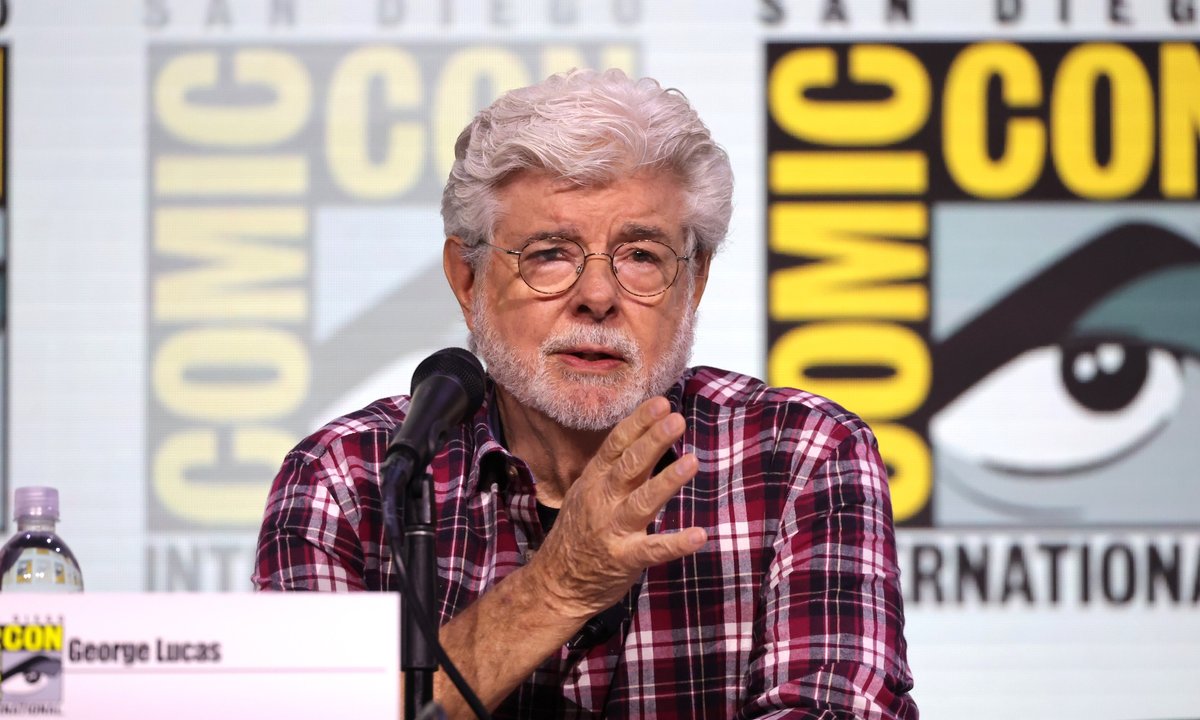

• Claes Oldenburg, born Stockholm 28 January 1929; married 1960 Patty Mucha (marriage dissolved 1970), 1977 Coosje van Bruggen (died 2009); one stepdaughter, one stepson; died New York Metropolis 18 July 2022.