“Whether or not I captured Apolonia with my digicam or whether or not she captured me in her theatre, I nonetheless don’t know,” says Lea Glob, the author and director of a brand new documentary that upends distinctions between artist and object, the viewer and the seen. A cinematic portrait of a portrait painter, Apolonia, Apolonia (2022) chronicles 13 years within the lifetime of Apolonia Sokol, an ebullient, irreverent artist raised by hippie thespians in Lavoir Moderne Parisien, a washing corridor turned experimental theatre within the working-class 18th arrondissement.

Punctuated by Glob’s quiet Danish voiceover, the movie offers a verité tackle each Sokol’s life and an underground artwork world imperilled by intensifying market forces. How can an artist—particularly a girl artist—make it today with out promoting her soul? And what should she sacrifice to take action?

The presence, and energy, of the feminine gaze—directed at others and at oneself—dominates all through. Within the opening shot, Sokol stares into an oval mirror and snips her darkish bangs with a pair of shears, bleach cream unfold above her frowning mouth. Accustomed to being in entrance of the lens from infancy (her beginning is actually caught on tape), she shows a patent absence of self-importance and self-consciousness, a refreshing flip from the “authenticity” paraded on social media.

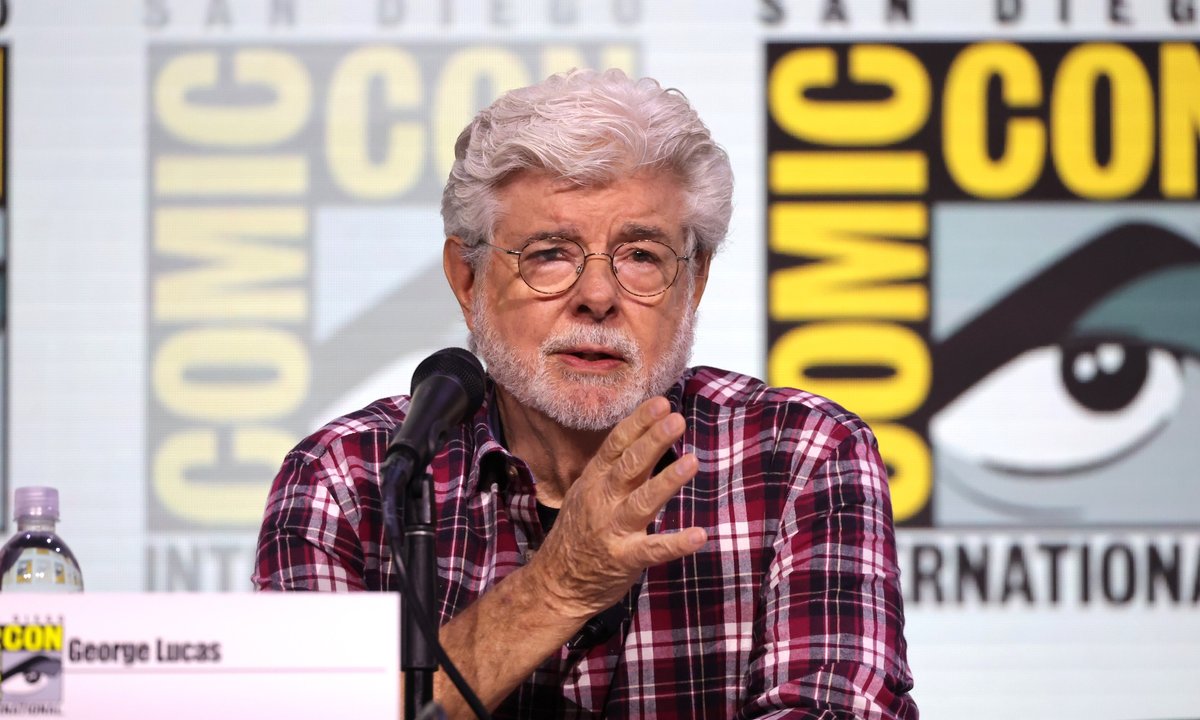

A scene from Lea Glob’s Apolonia, Apolonia (2022) Courtesy of Danish Documentary Manufacturing

Glob, who grew up in rural Denmark, serves as a foil to Sokol’s exhibitionist persona. “No motif has caught my eye as she did,” the director says. “She appeared acquainted and like a stranger on the similar time.” Sokol is portrayed throughout a sweeping vary of conditions and life chapters—from receiving the information that she’s getting dumped to telling her Polish grandmother that she is just not excited by having youngsters.

Many movies intention to seize the grandeur of being an artist, however few seize the truth that being an artist is much less outlined by grand epiphanies and on the spot validation than by the gruelling apply of attempting issues out, failing and attempting issues out once more, all whereas managing to feed, dress and home oneself. Sokol is depicted as feeding and housing not simply herself, however a group of artists and activists that squat on the Lavoir Moderne, together with members of Femen, the Ukrainian feminist revolutionary motion headed by Oksana Shachko, who turns into Sokol’s platonic residing associate.

The primary half of the movie chronicles Sokol’s wrestle to maintain the theatre that her dad and mom began. Between threats of eviction, arson and a violent assault by an viewers member throughout a efficiency, Lavoir Moderne’s bohemian utopia crumbles earlier than our eyes. Glob refrains from extreme exposition, such that the collection of occasions converse for themselves: Sokol doesn’t obtain the celebrated exhibition prize she aspires for on the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts; she is pressured to churn out work as quickly as doable by the Los Angeles-based seller and collector Stefan Simchowitz.

Whether or not she is caring for depressed, anorexic Shachko, or cooking for the chums whose portraits she paints, Sokol comes throughout as an artist who cares for different people as attentively as she regards her canvases. So, too, does Glob develop to genuinely look after her topic, whose monetary and psychological precarity for a lot of the movie appear to accentuate by the day.

A scene from Lea Glob’s Apolonia, Apolonia (2022) Courtesy of Danish Documentary Manufacturing

If something is obvious throughout the two hours we witness Sokol’s peripatetic strikes between Paris, New York, Los Angeles, Denmark and again, it’s that her work can’t evolve underneath draconian labour circumstances. Artists will not be machines; they break down, expire, want naps and smoke breaks to forestall collapse. Nor are artists “manufacturers”—or, if they’re, they’re so solely on the expense of their very own sanity and integrity. In some of the transgressive—and hopeful—moments of the movie, when she resides in Los Angeles, Sokol dangers arrest by disrobing in entrance of Paul McCarthy’s big butt plug sculpture. “Fuck America,” she says, earlier than pulling a nude again bend within the park.

At that very same time, the movie by no means capitulates to cynicism; nor does it kowtow to the pat redemption of the ability of artwork. Glob persists in making—and eventually ending—the movie after dwindling funds and her personal brush with loss of life throughout the beginning of her son. The digicam hovers over Glob as she gently smiles, her face buried in hospital tubes as her new child snoozes on her chest.

Apolonia, Apolonia honours the burden of creating artwork in a physique that itself has the ability to breed—and destroy itself in doing so. “The reality is, I by no means had management,” Glob says towards the top of the movie. Each topic and object of the gaze, the 2 ladies anchor what quantities to a deeply shifting feminist excavation of what it means to make artwork to be able to survive, and survive to be able to make. “I can’t separate what I do and what I’m,” Sokol tells Glob in Danish. “I can’t inform the distinction between my id and my work.”

Watch the trailer for Apolonia, Apolonia:

- Apolonia, Apolonia, 10 November at 3:15pm, Doc NYC, IFC Middle, New York