The French philosopher Gilles Deleuze once described university seminars as “a kind of Sprechgesang, closer to music than to theatre”. In theory, he said, there is nothing to stop one from being like a rock concert. And Vincennes, “the lost university” as it has since been dubbed, is where it all started.

The Centre Universitaire Expérimental de Vincennes was the short-lived educational experiment that Charles de Gaulle’s embattled government hastily announced in the wake of the May 1968 protests and civil unrest. It was demolished just 12 years later.

When rioting students and workers had taken to Paris streets, they had demanded, among other changes, democratic access to knowledge. The education minister Edgar Faure clearly thought that by parking the insurrection in the Bois de Vincennes—a wooded area in south-east Paris—it would simply go away. To those exercised young minds, though, the buses that took them to this new place of learning passed through a portal into a universe unlike any other.

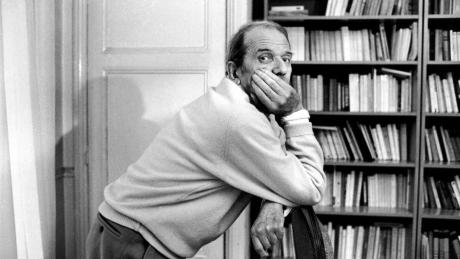

Michel Foucault and Jacques Lacan were founding faculty, Jacques Derrida was a consultant and Noam Chomsky a visiting lecturer. Deleuze, meanwhile, smoked his way through a series of exploratory deep-dives, in a philosophy department that rejected the notion of building up knowledge progressively.

He did not prepare notes, but he did rehearse his delivery. He was always adamant that no transcripts be published. The recordings, along with bootlegged transcriptions and unsanctioned translations, have nonetheless populated the internet for years. In 2023, the philosopher David Lapoujade, who acts on behalf of the Deleuze family, published the first official transcription, Sur la peinture, of the seminar on painting that Deleuze gave in 1981. Part of this was strategic: there is little of Deleuze’s writing left to publish. At the same time, the value of his spoken work cannot be underestimated. A book has even been written about Deleuze’s diction—gruff, generous, playful and impossibly erudite, but never stuffy.

The US literary critic and Deleuze specialist Charles Stivale, whose English translation, On Painting, is published this month, says that, in terms of transcribing Deleuze’s courses, painting is a good place to start as “it is the most accessible seminar by far.”

Deleuze brings in a host of artists—Caravaggio, Cézanne, Klee, Bacon, among others—to discuss painting as catastrophe, the point at which everything the painter sees falls apart, and the potential there is in that moment of imbalance.

More broadly, Deleuze does a deep-dive into colour and how it functions, which is central, not just to his understanding of painting, but of philosophy itself. He likened philosophy to colour, and the philosopher to someone who creates. First you have to do a lot of portraiture, of sketching out other people’s thinking, before you can start wielding your own colour, that is, your own concepts.

Midway through one of his sessions, titled Diagram, Code and Analogy, a student pipes up, saying the discussion has reminded her of a study on codes in Medieval sculpture. Deleuze gets excited and asks her to stand up and repeat her comment. Then he asks that she bring in her notes so he can read them. “See?” he tells the class, “there are tons of things I haven’t considered.” This is thought, at its most alive—and you are right there in the room with him.

• David Lapoujade (ed.), Deleuze, On Painting, translated by Charles J Stivale, University of Minnesota Press, 360pp, $34.95 (pb)