The search for peace, safety and perspective was front and centre for many artists in 2025, but Precious Okoyomon found all three in a rare place: behind the controls of a propeller plane, thousands of metres above ground. “Not everyone wants to be in a Cessna 120 feeling the vibration of every little thing that’s happening, but for me, it really resets my nervous system,” they told The Art Newspaper in early December, adding with mischief in their voice: “I like extremes, so I don’t mind things that can kill me.”

The conversation was jump-started by an October walkthrough of It’s important to have ur fangs out at the end of the world (until 17 January), Okoyomon’s first exhibition with the contemporary gallery Mendes Wood DM. The show, staged at the gallery’s permanent space in Paris, highlights the artist’s expanding practice. It includes sculptures of manga-inflected bears the size of large dogs, artist-designed wallpaper and a new fable written by Okoyomon, whose poetry is the bedrock of their creative output.

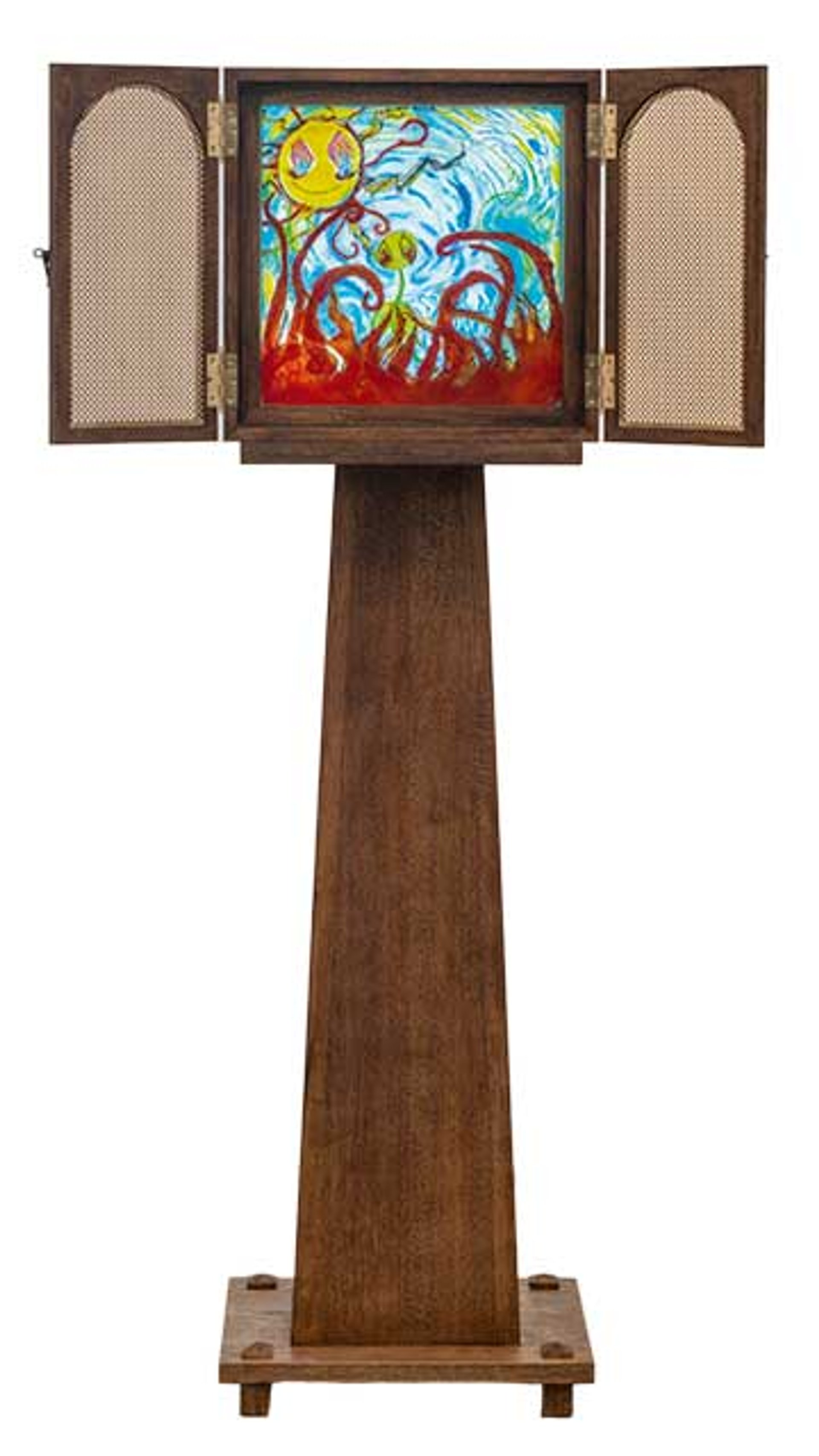

But it is the show’s three dioramas that directly invoke the artist’s experience as a recreational pilot. Painted in oils on glass panes and mounted in light boxes, the scenes depict a burning pastoral world populated by an anthropomorphic sun, flowers and more bears. They combine some of the core themes—our industrially poisoned ecology, the natural world’s resilience and the dire consequences for humanity—that underpinned Okoyomon’s installations at the 2022 Venice Biennale, a 2025 solo show at Austria’s Kunsthaus Bregenz and elsewhere.

“When I was making the dioramas, a lot of the sky study pictures I would take on my phone, which I’m just doing while I’m flying. I’m always witnessing and needing to archive,” Okoyomon says. “Certain things you can only see from the sky: how colours blend together, how the landscape looks.”

Okoyomon learned as much as a teenager. Their family relocated to suburban West Chester, Ohio, after stints in the UK (where the artist was born), Nigeria (where their parents grew up) and Houston. “I had experienced so many different worlds. Then, all of a sudden, I was in Ohio”—a place they were “not entranced with”.

In exchange for working in the only Nigerian restaurant in Cincinnati, however, Okoyomon’s mother agreed to pay for flying lessons at the nearby (and since-closed) Blue Ash Airport. It was a salve and a thrill; Okoyomon got their pilot’s licence before their driver’s licence. Lately, they have mainly flown when they return to Ohio to visit their mother. They are still searching for the right small airport near their home and studio in Brooklyn.

Flying nevertheless threaded the two locations together through the artist’s practice. The move east compelled Okoyomon to pen a series of poems called Sky Songs, and later to shoot a video work in which they read one entry from the cockpit mid-flight. “I wrote the beginning half of these poems when I moved to New York about trying to feel rooted or grounded,” they say. “I felt untethered, and in a way the only place I felt safe was in the sky, which is kind of crazy.”

Okoyomon’s Our love is a blue instant and forward-looking sky (2025), a lightbox inspired by the artist’s experience of flying planes

Courtesy of the artist and Mendes Wood DM; photo: Nicolas Brasseur

There is a very short list of artists who have doubled as pilots. The most prominent is James Turrell, the titan of light and celestial art. He learned to fly by the age of 16, rescued Buddhist monks from Tibet by air during the Vietnam War and has taken to the skies regularly over the decades since. (He discovered Roden Crater, the extinct volcano that has become the site of his still-unfinished magnum opus in the Arizona desert, from the cockpit.)

More common are the artists who have been fascinated with flight from the ground. After being drafted to serve in the Second World War, Roy Lichtenstein (1923-97) applied to train as an Air Force pilot but was reassigned. Panamarenko (1940-2019) centred his storied career on drawings, sculptures and quasi-functional objects pursuing flight in various forms. Okoyomon summarised the latter—with obvious admiration—as “a real weirdo” whose “crazy beautiful” contraptions have been an ongoing inspiration.

Then there is the German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen and his 1995 Helicopter string quartet, a piece that interweaves anxious string scales, tremolos and vocalisations with the chugging blades of four live, functioning helicopters. It is Okoyomon’s main reference point for their “dream of making an insane opera with planes—somewhere in the mountains, somewhere difficult”. It is the type of project that requires taking the long view. But where better to find it than in the pilot’s seat?

- Precious Okoyomon: It’s important to have ur fangs out at the end of the world, Mendes Wood DM, until 17 January