This autumn, the US Supreme Court docket will take into account whether or not you—artists, collectors, gallerists, historians, critics, curators, museum directors, educators—all of us as producers, stewards and the viewers for artwork, are related. Does your opinion of the importance of a murals have authorized worth? Does your capability to discern significant distinction between two visually related works matter?

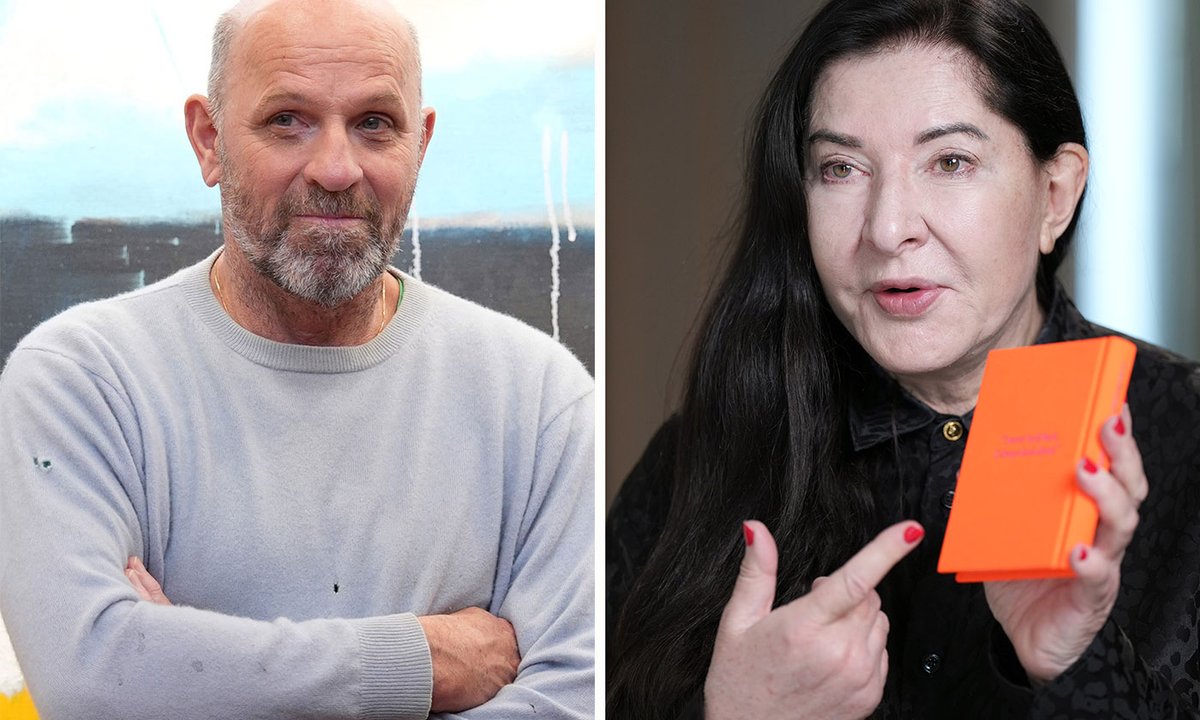

These questions are on the true centre of the dispute between the Andy Warhol Basis for the Visible Arts, which holds copyrights in artwork created by Andy Warhol, and Lynn Goldsmith, a photographer who might be finest identified for her portraits of celebrities.

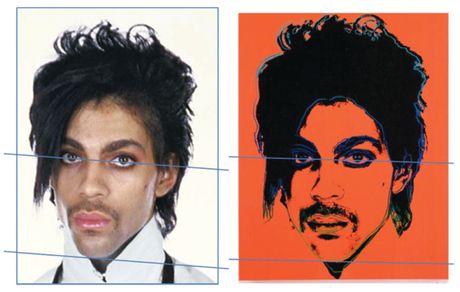

The dispute was triggered by Goldsmith’s objection to Warhol’s use of her {photograph} of Prince as a supply for his 1984 silkscreen print sequence. When Condé Nast used one among Warhol’s photographs on the duvet of a Prince tribute journal in 2016, Goldsmith asserted that her rights in her picture had been infringed. Anybody may see that Warhol had used her photograph as a supply, she reasoned, and so, she claimed, he ought to have requested permission and he or she needs to be paid.

The muse responded by asking the suitable New York district court docket to affirm that Warhol’s use of Goldsmith’s picture was honest, requiring no permission and no payment, as a result of the ensuing work had a brand new that means and message. That is the “transformative use” normal set by the Supreme Court docket in 1994 and utilized many instances since throughout the nation. The district court docket agreed with the muse, and a few of us thought that was that.

Then issues took a flip, in the end resulting in the Supreme Court docket’s uncommon resolution to listen to a case specializing in visible artwork. On attraction, the Second Circuit got here up with an unprecedented rule that it utilized to search out that Warhol’s works are infringing—although the court docket conceded that the that means and message of the works are distinct from Goldsmith’s.

The Second Circuit acknowledged that courts shouldn’t “search to establish the intent behind or that means of the works at situation”. As an alternative, the court docket fixated on the query of visible similarity and determined that as a result of Warhol and Goldmith’s photographs serve the identical perform—each have been “created as works of visible artwork” and are “portraits of the identical individual”—Warhol’s work is infringing as a result of it’s “recognisably deriving from, and retaining the important parts of, its supply materials”. In different phrases, except its visible relation to a different artwork supply is sufficiently obscured, the follow-on work is infringing.

You will need to perceive the sensible implications of this: if a decide can not look previous the visible similarity between two works and determine that the distinction between them issues, then you haven’t any enter. Regardless of how skilled, your opinion on the cultural or historic significance of an allegedly infringing work is irrelevant. You wouldn’t have a voice right here, regardless of your connoisseurship, your scholarship, your varied investments in artwork or your curiosity in a inventive ecosystem that may permit a Warhol to develop—or a Hans Haacke, Renée Inexperienced, Dara Birnbaum, Adrian Piper, Arthur Jafa or Alfredo Jaar, for instance.

This could disturb everybody. The historical past of artwork contains many works which can be visually related. If our capability to see significant variations between them is dismissed by the regulation, the outcomes are so weird that we’ve not been in a position to take them significantly—but.

If the Supreme Court docket doesn’t reaffirm its personal transformative honest use normal, it isn’t too far a stretch to say that our biggest private and non-private collections, to not point out many studios, galleries, textbooks and Instagram accounts, will immediately be crammed with illegal artwork. US authorized jurisdiction is not going to confine the repercussions.

It’s also vital to spotlight the insidious nature of copyright overreach. Nobody is arguing that creatives shouldn’t be moderately paid, however there’s too nice a value to the default “always-on” licensing scheme envisioned right here. The Supreme Court docket has repeatedly made clear that copyright doesn’t trump free speech. Asserting rights past these granted by the copyright regulation is nothing in need of an try and suppress freedom of expression. Warhol’s Prince isn’t Goldsmith’s Prince. Interval.

As a part of the Warhol Basis’s petition for a listening to, a number of “associates of the court docket” briefs have been filed by teams of copyright and artwork regulation professors, two outstanding artists and artwork professors, and the Robert Rauschenberg Basis and Roy Lichtenstein Basis joined by the Brooklyn Museum. As briefing for the Supreme Court docket listening to nears completion, all of us—and particularly US cultural establishments, their donors, patrons and people who sit on their boards—should recognize that it’s time to communicate up.

• Virginia Rutledge is an artwork historian and lawyer. She co-authored the amicus temporary in Cariou v. Prince, submitted in 2013 by the Warhol and Rauschenberg foundations, and endorsed by 29 main visible arts organisations throughout the US