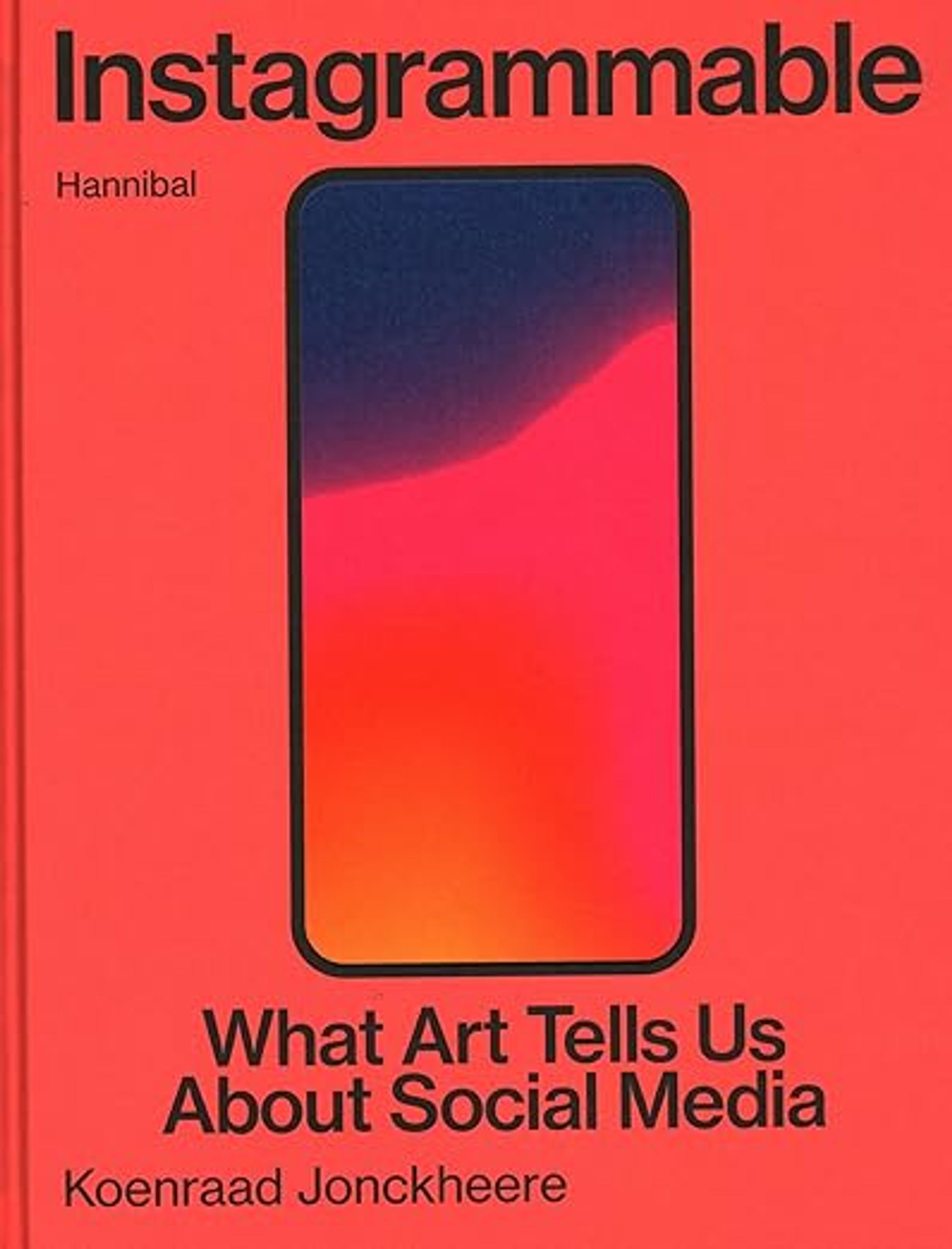

When it comes to art and images, Instagram is not new. So says the new book Instagrammable by the art history professor Koenraad Jonckheere. The book weaves together examples of Greek mythology and Classical philosophy with Judeo-Christian theology and Renaissance ideals to argue that the way we create and view images on Instagram today is in fact well established in history.

“Platforms like Instagram and other social media use age-old mechanisms that fuel our appetite for art and imagery,” Jonckheere tells The Art Newspaper. “These techniques have been studied in the West since as early as 500BC, and insights from antiquity, the Middle Ages and the Renaissance offer fascinating perspectives on how visual communication works today. Understanding these historical approaches provides valuable context for interpreting how we engage with visual media on social platforms.”

From sfumato to face tuning

Split into 12 chapters, the richly illustrated book uses art history to help explain the popularity of contemporary visual phenomena like filters, face tuning and hashtags. Jonckheere compares today’s image filters with Leonardo da Vinci’s use of sfumato, a technique of shading in painting and drawing that produces soft transitions between colours and tones. He argues that our use of editing apps that subtly improve our appearance are no different to the wealthy and important individuals who commissioned artists to create favourable portraits. Virtual influencers that promote make-believe lifestyles are the same, Jonckheere says, as the mythological allegories of ideal, moral lives that artists have painted throughout history.

Much of the book is a discussion of semiotics, exploring how we look at and interpret images. “There is more to an image than what you can see. There is always an interaction between observation, registration, and fantasy,” Jonckheere writes, describing this as “an age-old truth that has been forgotten in the rush to technology of the 20th and 21st centuries.” He notes that social media adds a fourth dimension to this trinity in that images online are “utterly devoid of any materiality” and therefore “are in a state of limbo, between counterfeit and imagination, undermining even more the tense relationship that has always existed between the world and its counterimages”.

This book will certainly draw people in through the shock effect of its pairing of ancient thought with something as contemporary as online platforms. (The first line of the blurb reads: “How are the Holy Trinity and social media related?” Wowzer.) While it reads conversationally—you can easily imagine parts being relayed as one of Jonckheere’s lectures to a room full of art history students, which of course they have—there is some presupposed knowledge of Classical mythology and philosophy (and an untranslated French phrase in the second sentence) that might make some want to give up before they’ve got past the first page.

But those who persist will enjoy an impressive meander through 2,500 years of critical thinking around images and art that reminds us that online platforms and digital media are not detached from history and humanity, and that images are not—and never have been—truth. It also lays important groundwork for social media as a subject worthy of art-historical study. “Instagram is a remarkable phenomenon. It differs from traditional visual history only in speed and scale,” Jonckheere says. “[It] serves as a bridge, helping students appreciate how historical visual techniques continue to shape our digital world.”

- Koenraad Jonckheere, Instagrammable: What Art Tells Us About Social Media, Hannibal, 312pp, 130 colour illustrations, published 22 November

Instagrammable: What art tells us about social media by Koenraad Jonckheere

courtesy Hannibal Books